Posted

Current State of SOPs: Do as we say, not as we do

If we look around our corporate environment, many employees within the enterprise can be classified as “knowledge workers.” Those employees are trusted to think, analyze, and apply scrutiny to information such that the best decions can be made, increasing the probability of a favorable outcome for the businesses they work for. Knowledge workers can be found across all business departments: operations, human resources, legal, accounting, and of course, cyber security.

Mature organizations recognize the value of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for knowledge works as a mechanism to:

- Achieve optimal business outcomes

- Promote consistency of processes

- Decrease the time of onboarding / training

- Improve efficiency

- Enable improvement

Within cyber security, the value of SOP’s are often sited in periodicals as a core necessity for more technical sub-processes, whereas procedures dictate the broader process that the sub-process are contained within. As a metaphor, a procedure might be defined for how a house is built, but an SOP might be defined for how lumber is cut.

While there is little debate as to the value of SOP’s within the broader community, they are inconsistently implemented and enforced by distributed cyber security teams. One root cause of this might be the absence of regulation that requires strict adherence to cyber security SOPs. This is likely to change in the future as organizational resiliency and corporate health continues to hinge more and more on he effectiveness of cyber security functions, and headlines draw awareness to more “wake up calls” in the aftermath of pervasive industry sweeping threats.

Enhancing SOP Reliability

Armies of knowledge workers can also be found within a fraud or economic crime tower. Compared to cyber security, the folks within this tower of business had their wake up calls a long time ago. And while every process can be improved, the anti-fraud industry has adopted some very good practices and achieved a level of maturity that cyber security is far from achieving. Much of this stems from tighter regulation around their processes and strict adherence to SOPs.

The following are some practices that can be considered based on the successes of anti-fraud SOP implementation as it relates to definition and enforcement of SOPs on cyber security teams. They are provided as a means to achieve greater reliability in cyber SOPs.

Introduce Points of Confirmation / Thoroughness:

Referencing one point of information is not the foundation for a strong decision in the best interest of an organization. When defining its must-search sources, and organization should not publish just one place to searched – rather multiple sources should be defined so that information can be corroborated and trust can be held in the decision made by an analyst. When data discrepancies between sources are identified, this creates the opportunity for scrutiny before a decision is made. An organization may require the following point of validation for different processes:

Use passive methods to thoroughly review and analyze links and attachments:

1. Access WHOIS utilities to find IP addresses and registration information of domains. Three points of validation are required.

2. Evaluate domains to determine if they have been reported as abused. Five Points of validation are required.

3. Evaluate hashes to determine if they have been reported / observed as malicious. Four Points of validation are required.

4. Check to determine if the domain / hashes have been identified as malicious and/or targeting the organization. Only one Point of validation is required.

Find related domains using OSINT on email addresses and other registration data.

Identify Must-Search Sources:

Balancing corporate culture and business objectives can be a juggling act. Many managers want to create an environment where folks can be creative, contribute towards or influence a process such that they feel a certain ownership of work-product and loyalty to the organization they work for. While admirable, this should not come at the expense of circumventing the steps that the organization has identified as the most effective process for investigating, escalating, and/or closing organizational incidents.

In fraud investigations, there are data and reference sets that must be searched.

Security procedures should be no different. The tools and information-sets that the organizations invests in are designed so that they can be used. Failure to use reliable information that is at our disposal constitutes an intelligence failure, and will not result in the best decision for the business. There can be no excuse for not searching these. Clearly defined must-search data sources might include explicit sources in these categories:

- Threat intelligence source(s)

- Historical Incidents

- Historical Tickets (e.g. IT)

- Internal Knowledge Bases

- Proprietary Data Sets / Databases

- Historical Events

- Trusted Identity Repositories

- OSINT Sources

- Social Media

Similarly, if there are sources that are not trusted by the organization, those should be identified and the team should be advised to expressly avoid them. For example, as a component of a phishing investigation SOP, an organization might include the following:

Use passive methods to thoroughly review and analyze links and attachments:

1. Access WHOIS utilities to find IP addresses and registration information of domains. Three points of validation are required. Acceptable sources include:

- Maxmind

- ARIN

- RIPE

2. Evaluate domains to determine if they have been reported as abused. Five Points of validation are required. Acceptable sources include:

- AbuseIPDB

- IPVOID

- PassiveTotal

- URLScan

- VirusTotal

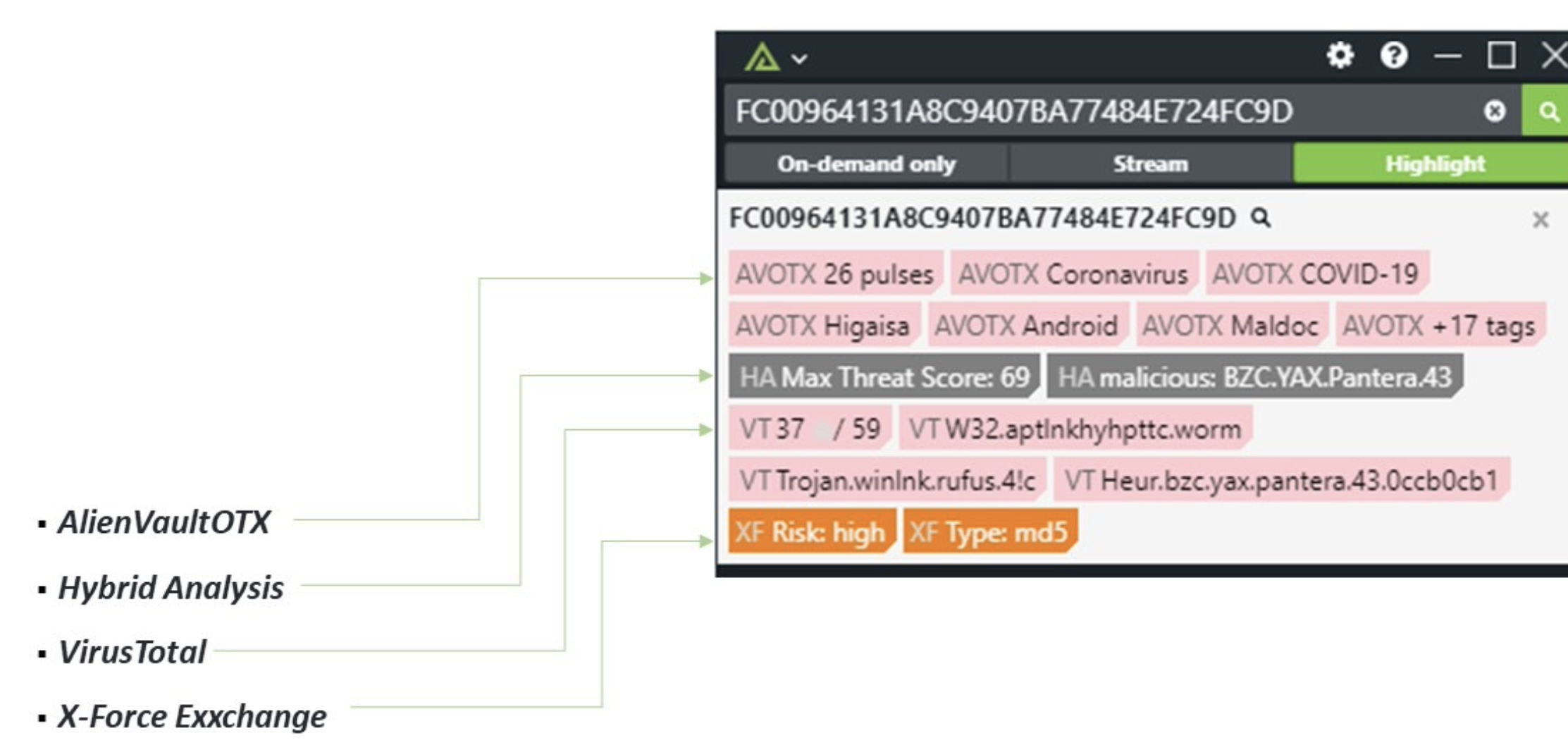

3. Evaluate hashes to determine if they have been reported / observed as malicious. Four Points of validation are required. Acceptable sources include:

- AlienVaultOTX

- Hybrid Analysis

- Malware Bazaar

- VirusTotal

4. Check to determine if the domain / hashes have been identified as malicious and/or targeting the organization. Only one Point of validation is required.

5. Find related domains using OSINT on email addresses and other registration data. Check at least two sources such as:

- Shodan

- Censys

For Polarity customers, the implementation of an SOP that requires multiple points of validation across must-search data sources can be seamless.

With Polarity, you can lock in your must-search data sources and ensure that multiple points of reference are searched uniformly on every investigation. In the example below, the following are brought to a team member on the fly as they do their work.

Check, Check and Check Again:

Some data sets that are defined as must-search sources may have been queried at a specific point in time when a data point was ingested – early in the ingestion process. If that is the case, the artifacts associated with the data point may be stale, and triggered automated processes may not have had the opportunity to take into account the most recent attributes of the data. As such, even if systems are leveraging some form of auto enrichment, it is still very important to check the must-search data sources to ensure decisions are being made with the most relevant information. The SOP should read along the lines of:

Our organization leverages internal and external data in the identification and assignment of severity for events and incidents.

If the indicators / actions / attributes of the event/incident under investigation have not been refreshed within 24 hours of initial creation, you should make an attempt to refresh such information and obtain the latest available information.

More Regimented Management:

Line management personnel should be empowered and have the mandate to define and enforce what tools, techniques and processes are to be followed by line personnel. All too often, line personnel are left with too much range insofar as determining which tools, datasets, and techniques they will be leveraging when investigating a corporate security incident. To bolster line management’s ability to enforce SOPs, the actions within SOPs should not be recommended – they should be mandatory. Using the prior example, one minor change from “should” to “must” enables management to enforce the SOP.

Our organization leverages internal and external data in the identification and assignment of severity for events and incidents.

If the indicators/actions/attributes of the event/incident under investigation have not been refreshed within 24 hours of initial creation, you must make an attempt to refresh such information and obtain the latest available information.

Mandated Feedback Loop:

When actions are mandated in SOPs and those actions include leveraging multiple points of confirmation, teams are in a position to contribute towards data quality.

If teams refer to 2 data sources, and the data sources directly conflict (e.g. Source 1: this thing is green, Source 2: This thing is red) that means that at least one data source is incomplete or entirly incorrect. We rely on knowledge workers to use the information they have available to determine which is more accurate and make a decision. Sometime this requires thinking out of the box, accessing new sources of information, reaching out to colleagues, physical inspection or observation. This ground work should not be wasted. The next knowledge worker on the next shift should not be required to do the same field work. It is inefficient and inconsistant. Instead, feedback loops must be introduced into processes and SOPs. Consider the following:

- In the event of incorrect information sourced from an approved external data set, report that information to line management.

- In the event of incorrect information contained within an internal repository (e.g. asset management platform, threat intelligence platform, identity management platform) report discoveries to owners of such platforms and copy line management.

- If you are unable to correct the information on the fly, or expect there will be significant lead time required to correct the information, record such information to a platfrom designed to make such corrections known to team members.

Reporting data quality issues in this way to help to improve process in two fundamental ways:

- It will give management visibility into the dependability of data sources.

- It will contribute to better quality of data and awareness of errors across teams, such that all personnel are making decisions based on the best information.

Prescribe Conflict Resolution Strategies:

In addition to reporting source conflicts or errors, teams should be aware of how to manage such conflicts when they are encountered. In other words, how should teams decide what information to trust and what not to trust. While this can be defined, management would be hard pressed to define a methodology for every scenario. As such, the minimum requirements should be defined, but an escalation path should follow immediately if the conflict cannot be resolved with confidence. Consider the following:

In the event of source conflicts, err on the side of caution. Evaluate the specific information available and make determinations prioritized based on:

- Vetted Sources – These sources of information have already been reviewed for data quality by members of our organization.

- Source Reliability – The trustworthiness of sources should be considered.

- Is the source commercially available?

- Is the source developed through qualitative measurement or qualitative means?

- Is the source community driven?

- Downstream source integrity

- Currency – When was the information collected or last updated? (Days, Weeks, Months, Years)

- Context – What is the reason you are reviewing this information? If it is to defend a critical asset from significant exposure, the risk of trusting an outside source may outweigh the risk of a misinformed decision.

In addition to defining the trusted/must-search sources, a process for handling discrepancies should also be documented within the SOP and socialized across a team. Not all sources are created equal. If 2 of 5 sources suggest a situation is X and 3 of 5 suggest a situation in Y, the analyst may be empowered to move forward with the expectation that the situation is X, if the 2 of 5 sources were most trustworthy.

Verbose Documentation:

Not too many operational security practitioners are all that jazzed up about documentation. However, the organization needs to be put into a state where clear lessons can be learned and applied in the event of an investigative misstep. Further documenting steps taken will provide evidence to external parties of investigative diligence, and foster adoption of the processes analysts should be following. Further, as processes become first hand, personnel will be able to identify ways to improve upon it.

That said, technology can be leveraged to a certain extent to reduce the burden of documentation. Unifying search results and establishing a mechanism to preserve a “point-in-time” artifact that demonstrates what was available to an analyst at the time it was made will go a long way in the event that a decision made during an investigation requires revisitation.

The details of the search process, including the results and deviations from the process, must be documented. The level of documentation is not left the the discretion of the analyst.

Audit-ability/Analytics/Improvement:

Documenting a decision making process is all well and good – and has the benefits previously described – but it does little for trend analysis over time. Just as though verbosity of logged events will support the security analysts’ ability to make quality decisions, so too will the verbosity of events demonstrating that investigative processes were followed.

Must-search data sources should provide an audit log of when they were searched, where they were searched from, and if they contributed to an investigative process. This type of logging can establish a foundation not only for a very defensible investigatory process, but also, a foundation for analysis to be applied in the pursuit of process optimization opportunities.

Regimented Process Does Not Exclude Inclusion

If teams deviate from process, they increase risk and create opportunity for failure. However, processes must evolve, and team input should be key influence of processes. A culture of inclusion can be embraced and team members can contribute towards process enhancement within a regimented process.

- SOP Bolt On’s: Allow your team to introduce additional steps into a SOP – provided it is in the spirit of the defined process.

- Opportunities to Shine: Give team members the opportunity to demonstrate technologies, data sets and/or techniques that they have discovered, explain why they are superior to those previously leveraged, and present the case for why it should be adopted into the process uniformly across a team or function.

- Codify New Processes in SOPs: If the team discovers a better way of doing something, have those that discovered or proposed the process enhancement document how the process should be included within the SOP.

Wrap Up (In Reverse Order)

Culture is very important, and constructive team member feedback is critical for process advancement – but if everyone is left to dictate their own personal process outside of structured SOPs, there will be a general inability to assure the processes are aligned to the achievement of optimal business outcomes.

SOPs should not be defined and managed as a guideline. They should be enforced as an organization would enforce other mandatory policies, leaving room for flexibility only within the areas of SOPs that require the most flexibility.

Polarity can help enforce adherence to organizational SOPs, and ensure that teams are following a consistent analytical process.

Further, Polarity can offer the means to contribute towards a feedback loop.

Finally, with Polarity Source Analytics, leaders can get visibility into the processes and identify bottlenecks, process gaps, and data quality deficiencies.